The following is the March Blog Post by John Howard Society Inclusive Community Artist in Residence Johnny Trinh. To learn more about Johnny’s Residency, visit the Artist in Residence page.

Stigma “a mark of disgrace associated with a particular circumstance, quality, or person” -Oxford Dictionary

Stigma- the walls around my residency.

Stigma- the dirty lens that prevents me from looking outside in.

Stigma- the unwanted offerings from generosity I never asked for.

Stigma- the distorted two-way mirrors installed the wrong way.

Stigma- the paycheque difference between me and a housing crisis.

Stigma- the nuanced opinions (unsolicited), readily offered by my family.

Stigma- the same opinions that I find out my participants receive as their stories are revealed.

Stigma- a changing state in decline, as we grow out of the boxes they put us in.

Stigma- the lessons unlearned by relatives waking up late, but finally waking.

I’m sitting in a Chinese restaurant with semi-distant relatives. The restaurant used to be a destination dining experience, Hennesey at every table, line ups out the door. I am told it recently switched owners. Everything is vermillion red, more accurately, I can tell that everything used to be vermillion red. The seat cushions are threadbare. The table cloths are pink. There is an LED Dragon and Phoenix hung against a red velvet backdrop that is bleached by years of excessive lighting. It blends into the rose-coloured carpet that surrounds our table. A cousin I’ve never met aggressively orders peking duck. He is loud. He wears high rise pleated pants, and an ill-fitting button down shirt. His behaviour reeks of dilapidation and disdain. Nothing is good enough. He works for a high-end media corporation, and does “consulting” from home. I decide that he fits in perfectly with this space, I’ve never met this person, and yet… I’ve met him so many times before. I am distracted by the waft of chilli-fried crab, crispy duck skin, and an off-the-menu scallop-fried rice. We are sitting with a table of our other cousins and distant aunties who are obsessed with telli ng us how grateful we should be for the risks they took.

They speak of immigration and the American dream. They hold on to this ideal of what Canada means, and if “you just work harder”, you’ll reach your goals. We argue, my eyes roll in synch with the lazy susan. We pause to sip jasmine tea.

“The homeless people don’t like me. I keep offering them food and they don’t take it.” My cousin says with shock. “Did you ask them if they wanted food?” I respond softly. The polarizing discussion of diligence overcoming systemic oppression has led us to the housing crisis in Vancouver.

“Well I ask them what food they want.” He responds defensively.

“But did you ask them if they wanted you to buy them food?” I repeat.

“No, I wanted to surprise them.” He waivers, unsure of my point, but perhaps more unsure of his position.

“We can’t assume to know why someone might be soliciting on the street, or why they might be homeless. But we can believe that everyone has a right to an opinion, and some agency in their life. In your generosity… you presumed to expect their gratitude for something they had no say in, and didn’t ask for. Your generosity, and their agency are two different things.” I push, it feels like a one-person army as my relatives rally.

“Even when I ask them, they can be mean, or say they don’t like something I’ve purchased for them.” His sister retorts.

“What’s wrong with them having preferences and tastes?” I reason.

“Well… they should be more grateful.” She sniffs. The mentality of “beggars can’t be choosers” exudes from her lips, as it’s unfathomable to her that anyone who has less, would reject whatever is offered. I steel myself, ready to battle this head on.

“No, Johnny’s right.” He says. “It’s like someone in a wheelchair- you wouldn’t just go up and start pushing without asking and expect them to thank you. You shouldn’t push them at all, unless they give their permission.” I top up his tea cup. It is the most respectful thing I can do in the moment. Breakthrough.

This opens up the table, and I talk about my work. Beyond doctor, engineer, teacher, nurse, or any mononymic job title, other professions don’t always compute within my family. Me, trying to do a 15 second elevator pitch on what a community-engaged artist is, is slightly more effective than my family trying to tell our other relatives what a community-engaged artist is. But I tell them of my work at the John Howard Society. They’re intrigued. They stereotype. We take a couple steps back, regressing into fears of thievery, substance use, and those “types” of people.

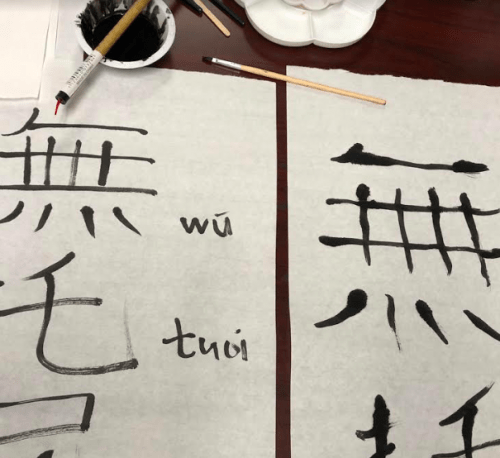

But I take the opportunity to share joy. I tell them about Chinese New Year’s at the John Howard. I tell them about learning/teaching Chinese Calligraphy and how much it resonated with the participants. We were able to share stories about how we were named. During our calligraphy session, many folks asked about writing their name in Chinese. We bonded over the process of phoneticizing a name (similar to how an Anglicized name is translated to Japanese), but more so over translating names based on meanings. I shared the impact of discovering how attached people were to their names. For many of the folks at the John Howard, they have multiple names in various languages. Timothy, who is Chinese, was already able to write his Chinese name, and even help other participants with their Chinese. We were able to bond over the similar experiences of being born with non-English names, and the reverse process of being Anglicized, integrated, assimilated because our parents wanted us to be successful or face less barriers.

My family is moved by my storytelling. I ask them for help with other characters, I tap into memories of Chinese School as children, and we inevitably tease each other for our varied levels of illiteracy. But I am reminded of the wonder, the initial spark when you learn your name, and how to better do that with new learners. The older relatives are supportive, any chance that the younger folks work to retain the language, and our culture, makes them happy.

I push further. I double down, as the wait staff bring us red bean soup (a common desert after meals at restaurants like these). I talk about what I’ve learned of Nis’gaa New Year. I share the history lessons, and research of Chinese migrant workers… secretly hoping that one of my older relatives will know or be able to trace us back to that time. Sadly, this information is not offered. But we are able to talk about how the host nations on this unceded land, how their ancestors helped our ancestors. How, no matter when/where you come from, you cannot survive on hard work alone, you need help. You need local help.

This month at the John Howard Society, I’ve moved from learning about the space, and its amazing programs, to bringing myself to the space. I’ve begun by sharing aspects of my ancestry and culture. Sharing food, cultural practices, personal stories… but I admit, the labour is intensive as I too break down and unlearn the stigmas my parents instilled in me. I am a product of the people at this dinner table. The process has been vulnerable, but incredibly rewarding, because in the offering with consent, the participants have offered their stories back. As our relationships fortify, I realize that I need more help. I need more local help.

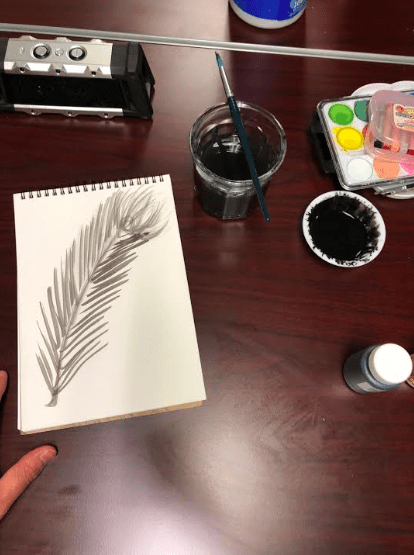

So, with excitement and wonder, I will be inviting amazing, local artists to come co-facilitate with me. Usually once a month, diverse artists will come and share practices and provide more opportunities for participants to articulate their experience. From theatre games, to collage making, to weaving, and more- our goal is to create something tangible that will represent this experience we’re sharing. Our dream is not only creating something artful, but recognizing that the more people we can involve, and the greater humanity we can recognize in each other, the quicker we will dismantle the stigmas that still pervade so much of our daily lives.