The following is the November blog post from Inclusive Community Artist-in-Residence Lindsay Wong. To read more about Lindsay’s Residency, click here.

In a recent drug overdose incident, a neighbour, Darren, ran screaming and sobbing through the halls of our building, yelling for help and pounding on apartment doors.

“Please, please! He’s my brother! He’s not waking up! Someone help! Call 9-1-1! If he dies, it’s all my fault!”

Moments later, I jolted out of bed at 1 AM, fumbled for my iPhone but I could not find it.

***

During a Ted Talk in 2014 in Vancouver, acclaimed author Neil Gaiman spoke about our innate love for scary stories and why they have appealed to human beings since Ancient Egypt, the Bible, and even classical Roman times. Gaiman pondered the psychological significance of scary stories on our psyches:

“We have been telling each other tales of otherness, of life beyond the grave, for a long time; stories that prickle the flesh and make the shadows deeper and, most important, remind us that we live, and that there is something special, something unique and remarkable about the state of being alive.

In other words, we tell each other stories to understand what it’s like to be fundamentally human, in order to overcome our real-life terrors and deepest fears. It helps to discuss our what ifs sometimes, especially through storytelling. Autobiographical stories frequently comprise of our greatest psychological terrors, whether real or imagined, i.e. zombies or overbearing mother-in-laws. When told honestly, these personal anecdotes showcase our innate subconsciousness wanting to overcome our struggles.

The stories we tell ourselves and our listeners encapsulate our greatest joy as humans: to be alive.

***

“Someone pulled a knife on me again on Broadway,” Shawn, a workshop participant said, as I asked him about his day. “But I ran away.”

“You must have been scared,” I said. “I’m sorry it happened to you.”

Pausing, Shawn avoided eye contact. “I don’t want it to happen again,” he mumbled.

Another participant, Benjamin, sensing Shawn’s hesitancy, chimed in about Vancouver’s street gangs and the initiation process on Fraser Street and Kingsway, and how potential members are supposed to either threaten or stab a random stranger with a knife. Shawn may have been the unlucky chosen one this time. When Benjamin was walking home a few nights ago, a group of five adolescents surrounded him and tried to rob him of his wallet.

“I fought them off and they ran,” Benjamin said. “But I’ve been living on the streets for a long time so I can take care of myself. Usually though, they can tell if I’m a street person by the way I walk. I’m sorry you’re scared, Shawn. But you just have to keep telling yourself that you’ll be okay. Tomorrow will be different.”

Another participant who sometimes stops by workshop likes to wear a Spiderman mask in his daily life; it protects him from the “bad guys,” he admitted. Dale is a bearded man in his late fifties with a shy, boyish way of speaking, but he believes that the iconic blue, black and red webbed mask lends him strength whenever he wears it. By putting on his mask, he automatically transforms into a fearless superhero.

“I’m Spiderman every day,” Dale said with sincerity. “I have his super powers and ability not to be recognized so I can go anywhere.”

I laugh because who wouldn’t want to have a secret power to conquer their fears. Who wouldn’t want to be Spiderman?

***

What triggers fear? In an article in The Smithsonian Magazine, Arash Javanbakht and Linda Saab explain that fear begins inside the amygdala of the brain before spreading throughout the body. Our fear response is either fight, flight, or freeze depending on whether we sense anger or terror. If we encounter a predator, our amygdala immediately warns us, flooring our nervous system with stress hormones.

Some of my JHSLM neighbours and workshop participants live in a perpetual and haunting state of fear. I can’t imagine what it’s like to have stress hormones flooding my body constantly. This means that many of my JHSLM neighbours have shifting social groups, where loyalties and alliances change. Their friendships cycles spin like merry-go-rounds. Neighbours and workshop participants lend each other money and give one another small gifts of candy and chocolate regularly. When Eve, who has arthritis, requires a walking cane, Jerry gives her an extra one of his. Paul generously gives Sandy a guitar and beginner music lessons.

Yet the slightest noises, changes to a schedule, booming rap music, or any random disruptions in their daily lives can cause outbursts among the residents. The walls are not soundproof at Fraser Street, so conversations in the privacy of apartments or in the hallways are usually public knowledge. I know when my neighbours leave or return to their apartments. I’m sure they can hear me clacking noisily on my keyboard into the strange hours of the morning. They hear me chatter on conference calls, discussing deadlines and plots and extraneous character development.

This also means that I hear their intensifying fears, hypersensitivities, and confessions late into the night. Phones ring at 4 AM. Sleepless voices, like ghosts, float into the halls and through the membrane of the walls. My neighbours are afraid of the future. Loneliness. Gangs. Spiders. Homelessness. School. Poverty. Losing their only network of family or friends for comfort. And of course, death of loved ones from overdoses.

***

“Please! You have to come NOW! You can’t let my brother die!”

Darren’s frantic screaming and crying amplified, as his door-pounding continued relentlessly.

By the time I found my iPhone, which I had somehow knocked onto the floor, I heard grousing car engines and the backdoor shoved open. Voices that were urgent but calm. Running footsteps like calvary hooves. The outreach workers from Miller Block had arrived. Someone was sent downstairs to the CSO to retrieve the overdose injection kit.

While the conversation buzzed next door, I fell asleep.

***

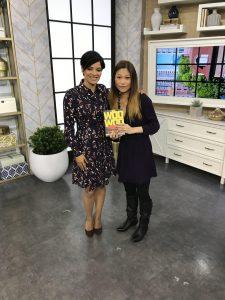

At the Vancouver Writers Festival, I also had to conquer my own fears (what I essentially didn’t know were spastic nerves when participating on a panel on writing memoir). My anxieties suddenly took me by surprise before the event on the Granville Island Arts Stage. My eyes started twitching, and I suddenly had the overwhelming feeling to flee. I did not realize that this panel would be presented to an auditorium of 200 people. I also did not realize that the well-read and intellectual David Lee, director of the JHS, was in the audience.

One of the experienced panelists, an older award-winning author, who had written more than three books, hugged me backstage, aware of my escalating nervousness.

“You’ll be great,” she said, encouragingly.

It will be over in an hour, I told myself, reitering my own narrative version of a happy ending and trying not to vomit on the esteemed author.

***

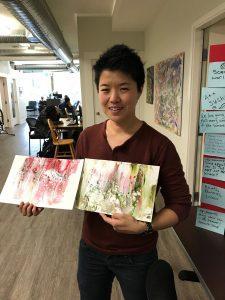

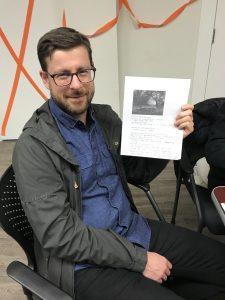

Our last workshop for the month was October 31. It was a fun, joy-laden Halloween-themed revelry with candy and chocolate bars and potato chips. Eric Rhys-Miller, the wonderful director of CACV, decided to join us for scary stories.

At first, participants were hesitant about telling spooky narratives and chose to opt for Halloween coloring and socializing; some watched Youtube videos on their phones or chatted with their outreach workers. When I asked our group to participate in story-telling, there was a resounding symphony of “no’s” until I offered to collaborate with them.

Darren, my neighbour and his on-again-off-again best friend and “brother from another mother,” Jonathan, told me semi-identical narratives that featured themselves as protagonists and heroes. They narrated similar stories about fighting a brutal family of flesh-eating zombies and triumphing in solidarity.

Darren was grinning and looked noticeably happier. I was glad to see that he was recovering from the drug-overdose incident. It had happened twice in the past month.

“We killed the bad guys by cutting off their heads!” Jonathan announced, laughing loudly and high-fiving his friend. Then they both dove into the candy buffet on the table.

Another participant, Emma, collaborated with me on a story about camping with seven best friends in the woods, but one of the friend’s was shot in the head because of a crazed man (ex-boyfriend) hiding in a bush.

“There was lots of bleeding everywhere. Then the ambulance came and saved the girl and she was okay,” Emma said, sounding hopeful. “She lived happily ever after at the John Howard Society.”

***

When asked to further elaborate on our fascination with scary stories, Neil Gaiman said: “In order for stories to work — for kids and for adults — they should scare. And you should triumph. There’s no point in triumphing over evil if the evil isn’t scary.”

We all want some form of a happy endings, no matter how impossible. And if we can conquer a few of our secret fears by fighting a zombie or a serial killer, we can comfort ourselves.

Readers, what are your fears and phobias? What stories do you tell yourself to cope or overcome them? Do you keep a journal? Please feel free to comment below.

Workshops will be held on Wednesdays Nov 28, Dec 5, 12, and 19 from 1-4 PM.

*Names of participants have been changed to protect their identities.