“Civic art, unfortunately, is one of the lost arts in

Canada, and we will not be able to claim any kind of social maturity until we

have recognized that our city not only must work well but most look well.”

– Peter Oberlander, architect and planner, 1960.

When it was established in 1950/51, the initial concern of the Civic Arts Committee was the improvement of the appearance of downtown Vancouver. It is almost impossible to imagine nowadays, even for people who were there at the time, what Vancouver looked like after World War II. A clutter of commercial signs dotted almost every building. The idea of open spaces was completely foreign to City Hall. On Georgia Street, car dealers advertised with plastic pennants and there were billboards everywhere. There were almost no trees in the downtown area and not a sign of any planting. The central core was littered with candy wrappers, gum, and other garbage. The forbidding canyons of buildings were deserted at night and on weekends. People who had once lived there had left. When attractive neighbourhood shopping malls began to develop, there was real concern among Arts Council members that downtown Vancouver was at risk and that drastic action was required to prevent its thorough demise. As Frank Low-Beer, an early council member, put it:

“At that time we were the only people around. I think it’s fair to say that the Arts Council and what the Civic Arts Committee stood for was the conscience of the city.”

Elizabeth Lane, another early member of the Civic Arts Committee, states:

“We had the most marvellous meetings during the fifties. We met in the New Design Gallery on Pender Street — the first contemporary art gallery in Vancouver run by Alvin Balkind and Abe Rogatnick, who had come from New York and stirred up the local cultural community. At that time everyone was so excited about what could be done.”

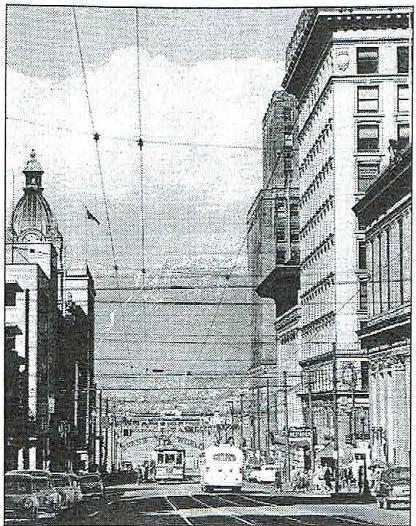

The Civic Arts Committee concentrated initially on the appearance of the streets. It lobbied for the installation of well-designed telephone booths, litter bins, bus shelters and benches. In 1959, new flower planters, at the entrance to the Vancouver Art Gallery in the 1200 block Georgia Street, probably contained the first live plants in the downtown area. The theory had been that nothing, including trees, could grow downtown because of gasoline fumes from cars. The committee successfully lobbied for street trees. Overhead electric wires and power poles were very intrusive, and the committee pressed for them to be put underground.

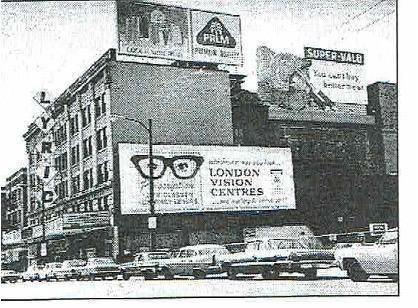

Much attention was paid to amenity streets, such as West Georgia and Burrard, where emphasis was on commercial sign control, street furniture of good design and street planting. The committee drafted a sign by-law and nudged city council continually to ‘halt the advance of the sign jungle.’ As a result, in 1956, (later amended many times) the appearance and size of signs on Georgia and Burrard were regulated. Billboards there were banned. In 1962, keeping up the pace, the Civic Arts Committee organized a mailing of hundreds of postcards to City Hall stating:

“Gentlemen, take away the setting and look at Vancouver objectively. It is becoming a hideous spectacle of sleazy signs and billboards. Soon there will be no scenery left to be seen… Driving vision is so fouled that signs are going higher to escape their own mess… act before it is too late. Affix 4 cents postage.”

After a few years’ interval these recommendations regarding obtrusive signs were accepted as a result of the briefs delivered at City Hall on various occasions by Civic Arts members, including Elizabeth Lane, Hilda Symonds, Peter Hebb and Sally Waddell. Vancouver at that time claimed more neon signs per capita than any city in the world. The Arts Council encouraged the use of colourful neon signs in the intensely commercial areas of Broadway, Kingsway, Granville and Chinatown, but suggested that they be regulated elsewhere, particularly on amenity streets.

The fact that today there are glimpses of Burrard Inlet and the mountains, and views from both the Granville and Burrard Street bridges is, to a great extent, due to the tremendous lobbying of Arts Council members to prevent the city from becoming walled-in by high buildings. Civic Arts member Elizabeth Jarvis presented a brief at City Hall requesting a by-law to be passed that no buildings should rise above any bridge deck. City Council accepted all the Arts Council recommendations, including a study to be done on bridge views.

The open space on north Georgia Street at the entrance to Stanley Park — that very choice and visible area which has been held in a park-like state — is the result of the Arts Council’s response, starting in 1963, to the threat of high-rise construction. For almost two decades the Arts Council lobbied to prevent the shoreline, from Denman to the park, from becoming monopolized by a series of planned developments, blocking views of the water, the greenness of Stanley Park and the mountains beyond. Over the years, various briefs to City Council concerning these intrusions on the urban landscape were initiated and presented by Blair Baillie on behalf of the Arts Council. A nucleus of Civic Arts members including Evelyn McKechnie, Dorothy Somerset, Dorothy Hebb, Betty Clyne, Betty Iredale and Frank Low-Beer, assisted in their deliberations by Arts Council member Hilda Symonds, formed the Save the Entrance to Stanley Park Committee. This aroused the politicians, the developers and the community at large, to the extent that the plans for development never materialized. Frank LowBeer remembers:

“We got a majority of local people to oppose it. Finally, there was a highwire act through litigation in the name of a local property owner. At the Arts Council’s urging, the city held a plebiscite which supported retaining the site as parkland. This did not stop the developers. The campaign went on for many years and eventually the city purchased the land through the Devonian Foundation. I think this is one of the great success stories of the Arts Council.”

In 1966 the Civic Arts Committee was again on the alert regarding city-owned Blocks 51, 61 and 71. A plan was proposed to build a provincial courthouse on Block 71 and a high-rise of 55 stories for provincial offices on Block 61, immediately north. The extreme height of the office tower did not please Arts Council members, so they commissioned Erickson-Massey Architects, who donated their services, to make a scale model proposing a new design for Block 61. In order to publicize this design, the Arts Council’s angel of mercy, Iby Koerner, invited civic officials, politicians and architects to her house for lunch, where the model was a prominent feature. Later it was in the Vancouver Public Library in a display called Downtown Dead or Alive. Arts Council intervention at this critical moment paid off. The original plan was dismissed and Robson Square, designed by Arthur Erickson, was the result, with landscaping by Cornelia Oberlander, and later with the old Court House restored as the Vancouver Art Gallery.

A proposal to demolish Christ Church Cathedral was aired in the late sixties, consisting of a plan to build a skyscraper on the entire site, including the side garden, and relegating the cathedral to an underground location. The Arts Council vehemently opposed this scheme and Civic Arts members, supported by heritage architect Harold Kalman, appeared before City Council expressing their concern. It is difficult today to imagine Vancouver without this historic church, described by an Arts Council member at the time demolition was threatened, as ‘the soul of the city.’

Waterfront views, as well as access to the waterfront for pedestrians, has been an enduring concern of the Civic Arts Committee. The development of False Creek and Granville Island, with ample open space for the public to enjoy the waterfront, was one of their recommendations. They lobbied for artists’ studios and for visual arts space to be included in the overall Granville Island Plan, Subsequently, federal minister Ron Basford who masterminded this successful Vancouver amenity, was given a special Arts Council award of merit.

A planning issue with a heritage flavour was brought to the attention of the Civic Arts Committee in 1980. It was becoming evident that the larger properties in the First Shaughnessy residential neighbourhood, a 440-acre area established in 1912, were threatened with redevelopment. In order to prevent the loss of individual, impressively large properties with their heritage houses and landscaping, the Shaughnessy Heights Property Owners’ Association intervened. Arts Council member Joyce Catliff brought this situation to the Civic Arts Committee requesting support for a proposed new by-law. This was to allow the infilling of large properties, including multiple conversion of dwellings of specified size and of a design compatible with the existing heritage structures. At a public hearing, a brief from the Arts Council supported the new by-law by creating, as Joyce Catliff described it, ‘a climate of concern’ within the community for the intrinsic heritage values in specific city neighbourhoods. The First Shaughnessy Advisory Design Panel is currently a very active and successful official civic committee.

Through the years, the Civic Arts Committee was assisted by its member, Bob Carey, who kept watch at City Hall on a regular basis, attending urban planning meetings and alerting the committee to upcoming issues. Similar conscientious efforts were made by a small group of members, appalled by the rundown condition of main streets, plazas, and sidewalks. Organized by Rudi and Eleanor Laser, they took early Sunday morning walks, photographing evidence of hazardous and unsightly decay. Calling themselves the ‘Pothole Committee,’ their slide presentations were well received by the City Engineer at a special City Hall presentation.

In January 1989, Frank Low-Beer, speaking for himself and like-minded Civic Arts members, wrote in some detail to Marathon Realty about developments on Coal Harbour, expressing concern over the preservation of ‘the direct presence of the water’ as well as its ‘visual access’ for those who daily use downtown streets. Arts Council members continue to follow this urban waterfront issue as the city grows and vast change occurs.

In the spring of 1989, the Arts Council became aware that the old CKWX Building at 1275 Burrard Street was slated for demolition, and with it the glass tile mural on the interior walls by the late Vancouver artist and UBC professor, B.C. Binning. In an emergency effort coordinated by Civic Arts Chair Shelagh Lindsey, supervised by conservator Andrew Todd, and supported by members of the City Planning Department, the City Archives, the site developer and UBC Dean of Arts, Robert Will, the Binning Mural was removed and transported to safe storage at UBC all in the space of four weeks.

Some Civic Arts Committee chairs:

- Blair Baillie

- J.E. Devereaux

- David Devine

- Alan Fetherstonhaugh

- Kathryn Hanson

- Betty Iredale

- Rudi and Eleanor Kaser

- Elizabeth Lane

- William T. Lane

- Bill Leithead

- Shelagh Lindsay

- Frank Low-Beer

- Graham McGarva

- Peter Oberlander

- Robert F. Osborne

- Mary Roaf

- Moira Sweeny

- Hilda Symonds

- Terry Tanner

- Louis van Blankenstein

- Geoffrey Woodward

In 1990, with Alan Fetherstonhaugh and Anthony Norfolk taking the lead, the Arts Council co-sponsored a forum which was to have a direct impact on the final Downtown South zoning plans. Developers, architects and community groups met to discuss and consider issues relating to density, design public access and open space.

Throughout the years, individual Arts Council members have continued to compile and present carefully researched briefs on leading cultural issues, for example those regarding the Status of the Artist in B.C. and the city’s Arts Initiative. The problems confronting the Vancouver Museum were researched in detail and recently presented to city consultants by Past President and current Vice-President of Advocacy, Blair Baillie. After several years of relative inactivity, the Civic Arts Committee has recently been revived with the new title, Urban Issues.