“Since a museum is one of the few places where you can

still be proud of being human, you can hardly dismiss it as dull and useless. A

good museum breeds generosity and curiosity and a bad museum kills it.”

– David Brock, writer and broadcaster, in the Arts Council News, 1965.

Late in 1963, a group of Arts Council members began to direct their concerns toward serious gaps in Vancouver’s museum facilities. Most citizens were only vaguely aware that there was a severe problem of lack of space at the existing City Museum on Main Street, now the Carnegie Centre. The Vancouver Art Gallery did not provide the facilities for a decorative arts museum and the City of Vancouver had no facility for storage of archives. Civic collections of Aboriginal art were scattered among the Museum, the Library, the Art Gallery, the University of British Columbia and the Pacific National Exhibition. The Maritime Museum, which had been Vancouver’s 1958 Centennial project, was one of the ten institutions in the city that held museum artifacts, but no coordination existed between any of these facilities.

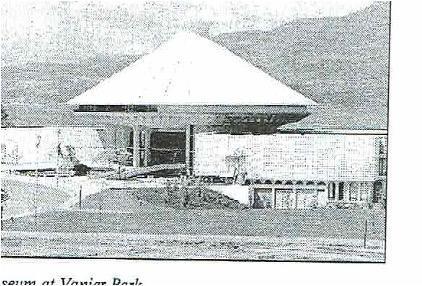

In 1964, the Arts Council gathered together a Museum Committee from the Civic Museum Board, the Art Historical and Scientific Society, the Vancouver Art Gallery, the City of Vancouver Archives and the University of British Columbia. A grant from the H.R. MacMillan Family Fund was received by the Arts Council, making it possible to commission Dr. Theodore Heinrich, a world renowned museum expert. Formerly with the Metropolitan Museum in New York and past director of the Royal Ontario Museum, Dr. Heinrich, made several visits to Vancouver to study and make recommendations on the city’s museum needs. His report, presented in May 1965 to the Arts Council, created general excitement because he strongly recommended that a new museum of natural and human history be built at Vanier Park, then known as Kitsilano Point. He considered this site “the most dramatic and appropriate setting in North America for a museum complex.” The plight of the particularly valuable artistic representations by First Nations peoples and their ancestors, so badly housed and cared for, was of great concern to him.

He identified two further areas of concern:

“The second shocking gap is the neglect of the fine arts of Asia. A third and disastrous gap is in European and decorative arts. Everyone knows that Vancouver and Victoria are happy hunting grounds for antique collectors; but neither visitor nor local citizens wishing to study authenticated objects in the Vancouver museums can experience anything but frustration.”

His recommendations made headlines in Vancouver newspapers, with his vision for a museum complex at Vanier Park including a comprehensive museum, a planetarium and a link with the Maritime Museum. He and Arts Council President Ralph Flitton made speech after speech in hotels, church basements, ladies clubs and Chamber of Commerce meetings and lobbied politicians of all levels to promote this new museum idea.

An additional incentive was City Archivist Major J.S. Matthews’ promise to donate three truckloads of precious pieces of Vancouver history if the complex went ahead. The most crucial development in early 1965 was the Federal Government’s donation of the R.C.A.F. base at Kitsilano to the City of Vancouver. This fortuitous event strengthened Dr. Heinrich’s proposal by providing much needed storage space for the new complex.

On June 9, 1965, City Council, after many near defeats and cliff-hanging decisions (there were many centennial proposals) proved the Heinrich Report in principle had accepted the first stage of the proposed new museum at Vanier Park as the Centennial Project of the city. Later in June, Gerald Hamilton and Associates were selected as architects. In 1968, the new Vancouver Museum opened to great fanfare. Arts Council volunteers arranged the Gala Opening Hall, a once-in-a-lifetime event made possible because the galleries were still vacant. A sophisticated light show coordinated by the design firm of Hopping, Kovach, and Grinnell illuminated the bare walls with magical changing colors. Mayor Tom Campbell made a congratulatory speech.

Dr. H.R. MacMillan’s generous personal gifts made possible the incorporation of the planetarium into the overall museum design. The ‘women of Vancouver,’ through Centennial Committee members Mrs. Wallace (?)oburn and Mrs. Charles Hillman, commissioned the stainless-steel George Norris crab sculpture at the entrance. The Junior League of Vancouver’s Centennial Project was the Junior Museum and the league also provided funding to hire the first Education Director Shirley Cuthbertson. Two magnolia trees from the grounds of Vancouver Court House were salvaged and planted several months later at the museum entrance, thanks to the determination of Betty Clyne and Clive Justice.

Initially the museums (the Vancouver Museum, the H.R. MacMillan Planetarium, and the Maritime Museum) were under the direction of the appointed Vancouver Civic Museum Board, directly responsible to City Council. Elizabeth Lane was a member of this board and was also elected chair of the Vancouver Museums Association incorporated in 1972, a newly formed independent body to direct operations of the new museums. Arts Council President Ralph Flitton and other Arts Council members subsequently became members of the Museums Association.

The museum complex has had its triumphs and its problems since this initial excitement. Recently the Maritime Museum, the Planetarium and the Vancouver Museum have gone their own separate ways under voluntary elected boards.

In 1995, City Council commissioned Sears and Russell, Museum Consultants from Toronto to examine every aspect of the Vancouver Museum in view of administrative and financial problems. As a result of this study many recommendations have been approved by City Council, all of which indicate a brighter future for the museum. The Arts Council played an active part in these deliberations through its Vice-President of Advocacy, Blair Baillie.

In 1971, the fabled Major Matthews died. By then the need for a building to house the City of Vancouver Archives had become urgent. An Arts Council committee was formed including representatives from libraries, universities, the Vancouver Museum, the Vancouver Historical Society and others to promote the idea of a Civic Archives to house both official and city records, photographs and memorabilia. A steadfast supporter intent upon seeing the completion of the civic archives building was City Clerk Ron Thompson who had been worrying for years where to house all the City Hall archival material.

A public meeting was called by the Arts Council and held at the new Vancouver Centennial Museum. Dr. W. Kaye Lamb, the chief archivist of the Dominion Archives of Canada, gave the address, which included recommendations advocating that the new archives building become Vancouver’s B.C. Centennial Project. His suggestion that the archives be situated at the Vanier site became a reality when what is often referred to as ‘The Major Matthews Archives’ was officially opened on December 29, 1972. Again, it was volunteers from the Arts Council who organized a celebratory gathering.

The Arts Council’s Phyllis Ross was an active member of the first Archives Advisory Committee. She worked to encourage pioneer families to give financial assistance or to donate papers. Today a Civic Archives Advisory Committee and a Friends of the Vancouver Archives Society support the Archives, a direct responsibility of the city, efficiently and pleasantly directed by City Archivist Sue Baptie. It is the only Canadian civic archives housed in a building specifically built for the purpose.